Share your thoughts in a quick Shelf Talk!

The Obscene Bird of Night by José Donoso

In a crumbling mansion haunted by rumor and memory, reality unravels into myth. The Obscene Bird of Night is a nightmarish labyrinth of voices and visions—an unsettling, hypnotic exploration of identity, power, and the stories that trap us.

Have you read this book? Share what you liked (or didn’t), and we’ll use your answers to recommend your next favorite read!

Love The Obscene Bird of Night but not sure what to read next?

These picks are popular with readers who enjoyed this book. Complete a quick Shelf Talk to get recommendations made just for you! Warning: possible spoilers for The Obscene Bird of Night below.

In The Obscene Bird of Night, did you enjoy ...

... an obsessive, reality-warping narrator whose annotations overtake the text?

Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov

If Mudito’s shifting I/he voice and the way his tale rewrites the reality of Jerónimo de Azcoitía’s household drew you in, you’ll love how Charles Kinbote hijacks John Shade’s poem in Pale Fire. Kinbote’s footnotes don’t just explain; they replace the story with his own grand fantasia of Zembla—just as Mudito’s accounts of the Casa and the “Boy” distort what anyone else might call facts. That pleasure of doubting every line while being pulled deeper into a mind’s invention is the same intoxicating game here.

... a fractured, time-slipping descent into a haunted estate and its chorus of voices?

Pedro Páramo by Juan Rulfo

If the labyrinthine Casa—half convent, half mausoleum—hooked you with its echoing whispers and broken timelines, Pedro Páramo delivers a similarly eerie collage. Juan Preciado arrives in Comala chasing his father and finds a town speaking in murmurs of the dead; scenes fold backward and sideways the way Mudito’s accounts of the Azcoitías and the hidden “Boy” keep reordering themselves. That same feeling of walking through rooms of the past where the walls talk is alive on every page.

... nightmare-logic, folkloric grotesquerie, and identity folding in on itself?

The Third Policeman by Flann O'Brien

If the imbunche myth, sewn mouths, and body-as-prison imagery in Donoso’s novel thrilled you, The Third Policeman is a perfect next nightmare. Its nameless narrator wanders a countryside where bicycles and men trade atoms, policemen enforce physics like theology, and identity loops into an eternal trap—an uncanny rhyme to Mudito’s self-erasure and the Casa’s grotesque rituals around the “Boy.” It’s that same dream logic where each explanation only deepens the unease.

... an intense, claustrophobic interior unraveling of self?

The Passion According to G.H. by Clarice Lispector

If you were gripped by Mudito’s self-dissolution—how being the Azcoitías’ mute secretary becomes a kind of vanishing—Lispector’s The Passion According to G.H. stages a single consciousness unmaking itself in real time. In a maid’s room, G.H. crushes a cockroach and then spirals through an ecstatic, terrifying meditation on identity and emptiness. That same ruthless, intimate pressure that Donoso applies in the Casa’s chambers is turned inward here, sentence by sentence.

... grotesque, allegorical bodies exposing a society’s rot?

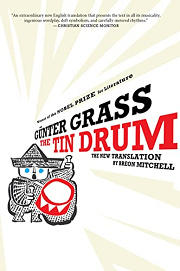

The Tin Drum by Günter Grass

If the hidden, deformed “Boy” and the Casa’s staged illusions worked for you as symbols of class rot and moral decay, The Tin Drum offers a similarly ferocious allegory. Oskar Matzerath wills himself never to grow, shatters glass with his scream, and drums through a collapsing Europe—his body and voice as charged and unreliable as Mudito’s testimony about Jerónimo de Azcoitía’s project. It’s that blend of carnival grotesque and social indictment you’re craving.

Unlock your personalized book recommendations! Just take a quick Shelf Talk for The Obscene Bird of Night by José Donoso. It’s only a few questions and takes less than a minute.